Not long ago, a friend of mine reported that she had become “spiritual” — but was no longer “religious.” She thinks “spiritual” thoughts from time to time, she explained. She notices “spiritual” attitudes or impulses creeping up on her, in a general sort of way. She feels oddly warm at times like these and a little more calm than usual. “Spiritual.” But no longer “religious.”

On the one hand, my friend doesn’t want to identify with any particular church or tradition: she does not want to appear sectarian. I can understand this concern. At a deeper level, however, my friend means something more simple, I think, and rather less defensible. She has dichotomized her life. From now on, she will emphasize the oddly warm “spiritual” things that attract her; her actual, work-a-day life, however, will belong to another department.

I remembered this interchange just the other day, while visiting with another friend about his prayer life. My friend believed in prayer, he wanted me to know, in a general sort of way. He practices prayer in church. Yet it never occurs to him to actually pray outside of his weekly routine — for some need that he encounters during the day, let’s say, or some friend that he meets on the street. “Maybe I should try it,” my friend confessed. “I am a pastor, after all,” he reflected.

Another friend confesses a similar attitude toward acts of service or evangelism. He believes in these activities, he tells me, in a general sort of way. “Spiritual” impulses creep up on him sometimes, too. But most of the time the impulses are pretty abstract: “spiritual,” I suppose, but not so very “religious.” They have little to do explicitly with life.

Sometimes, I fear, we have abstracted our spirituality to death. It is high time then for Christmas.

The message of Christmas makes the distinction between faraway “spiritual” things and this-worldly “religious” things impossible to maintain. The message of Christmas explodes the dichotomy completely. The message of Christmas, after all, is not about Santa Claus and candy canes.

Christmas announces the Incarnation, absolutely astounding, of God Most High in the wonderful Baby of Bethlehem. The Spiritual Reality behind everything, everywhere — the Creator and Sustainer of all things — has become a human being.

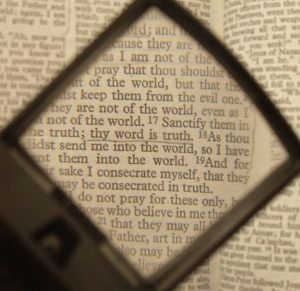

Heaven is no longer an abstraction. We may never again consider God a concept or philosophy. The Creator himself has shown up in our neighborhood, taken on flesh and chosen to dwell among us (John 1:14). Abstractions and dichotomies are no longer allowed.

The message of Christmas is about a Child, and his dear mother and dad. It is about a place. It is about an historical context, a particular time, a family and tribe — a Baby, then a Boy, then a Man — with his friends and detractors, hopes and fears, scrapes, calling, teaching, miracles, cross, empty tomb, and coming again. It is about Jesus Christ, God’s Only Son, our Lord, conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary… and made man. It is about real, historical lives become the locus of salvation.

Christmas people don’t come to faith or live it out in abstraction — but in the concrete world that surrounds them. This is where our spiritual lives are demonstrated, our prayers are offered and answered, and our occasional “impulses” to service and witness take on flesh and blood.

We might prefer to keep our faith abstract, I suppose: our “spiritual” lives are more comfortable that way. Then we can “believe” in prayer without praying, or in the idea of service without serving. Then we can feel oddly warm about “spiritual things” without getting our lives explicitly involved.

And then it is time for Christmas. Listen to the message once again, now at the end of the year. Listen carefully. You will find no abstractions in this story. You will find the Child of Bethlehem, calling you again to awe and faith and surrender. And you will find that he will lead you, if only you let him, from the manger into the world.