How does one get to South Sudan? (You will find the destination described in the preceding article.) How does one get to the rugged tribal territories of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa? How do you find your way to the border crossings that traffic girls from the mountains of Nepal to the brothels of Mumbai, or the huddles of glue sniffers in the slums of Nairobi, or the broken families so common at the margins of Guayaquil? Jesus is at work in these crossings, margins and slums. How do we follow him there?

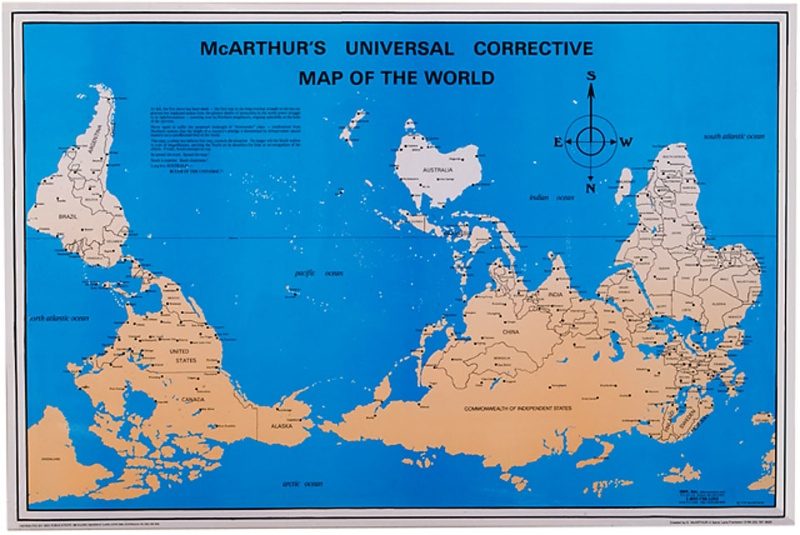

You might find a map to guide you, I suppose. Maybe you can “google” your way. But I doubt it. This kind of path must be made in our hearts, first of all.

Culturally speaking, we are not so disposed to margins and crossings like these. Over the summer, I have read a marvelous book by Ross Douthat provocatively titled, “Bad Religion” (New York: Free Press, 2012). Douthat chronicles the many ways that American Christianity has departed from its orthodox, Biblical, Christ-centered and mission-oriented root to become… well, “bad religion.”

One of our departures, in Douthat’s estimation, is a significant turning inward – toward our own fulfillment, personal satisfaction, and spiritual and financial wellbeing – as if these things were somehow our undeniable right. We have turned from risk toward security, from daring and uncertainty toward comfort. We have come to think that people like us deserve to be happy and unbothered. In the bargain we have lost our way to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – and to the Jesus who may call us there.

Douthat cites a recent study by Christian Smith and Patricia Snell, examining the spiritual lives of “twenty-something” Americans:

The majority of those interviewed stated… that nobody has any natural or general responsibility or obligation to help other people…. Most of those interviewed said that it is nice if people help others, but that nobody has to. Taking care of other people in need is an individual’s choice. If you want to do it, good. If not, that’s up to you. Even when pressed – What about victims of natural disaster or political oppression? What about helpless people who are not responsible for their poverty or disabilities? What about famines and floods and tsunamis? – No, they replied. If someone wants to help, then good for that person. But nobody has to.?[1]

This is a kind of “narcissistic spirituality,” in Douthat’s estimation – and it has waxed in recent years while empathy has waned.?[2] There is “nothing remotely countercultural” about this inward-directed spirituality: it has nothing distinctively Biblical to tell the culture that surrounds it. Indeed, this is a spirituality that tells “an affluent, appetitive society exactly what it wants to hear: that all of its deepest desires are really God’s desires, and that He wouldn’t dream of judging.”?[3] This is not the way to the slums of Nairobi.

There is a way, however: Jesus is himself the Way.

The writer to the Hebrews, as edgy as they come, reminds us that Jesus establishes the altar of Christian faith “outside the city gate” (Hebrews 13:12, NRSV). Mary did not lay the manger in the royal nursery, after all. Herod did not plant the cross in the gilded Temple of Jerusalem. From beginning to end, Jesus lived and gave his life “outside the gate” – outside the domain of tame, comfortable, inward-turning religion. Are we wanting to follow him? This is where he leads.

“So let’s go outside,” the writer to the Hebrews continues, “where Jesus is, where the action is – not trying to be privileged insiders, but taking our share in the abuse of Jesus. This ‘insider world’ is not our home…. Let’s take our place outside with Jesus….” (vv.13-15, The Message).

Douthat is right about the “bad religion” that has overtaken so much of our modern Christian world. Yet we cannot cure it by redoubling our effort at faith or obedience. We cannot pony up compassion. We cannot, simply, will ourselves willing to care for the slums of Nairobi. The map to Nairobi does not work this way.

This kind of path is made by encounter with Jesus. He himself becomes our Pathway – a Pathway that leads always outside. Sometimes, yes, to South Sudan.

[2] Ross Douthat, Bad Religion (New York: Free Press, 2012), p.235.

[3] ibid., p.236