Recently I have browsed again The Bondage of the Will, by Martin Luther. The book is a bracing experience.

Recently I have browsed again The Bondage of the Will, by Martin Luther. The book is a bracing experience.

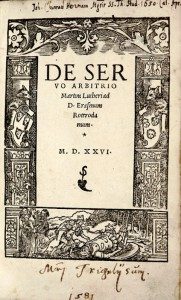

The Bondage of the Will was published in 1525 in reply to Desiderius Erasmus, who had published On Free Will the year before. That volume presented the traditional Roman Catholic position, more or less. Erasmus argued that human beings are free moral agents capable of choosing good or evil quite as they please. They are free to work out their own salvation by the choices they make throughout life. The grace of God, yes, assists them in the project. But basically they do it on their own.

Luther saw things differently. Human beings are not capable of choosing good in any consistent way at all, or “working out” salvation on their own. For Luther, sin is more deep-rooted than this, and the grace of God more radical and wild. God’s grace is nothing like an “assistant” in life. It is the vast, extreme, overwhelming love of God in Jesus Christ that makes our lives altogether new – and our wills, too. Grace creates faith and animates holy choices, not the other way around.

The Law and Gospel, Luther explained, put this basic dynamic into action. The commandments of God are given “in order that through them the proud, blind man may learn the plague of his impotence, should he try to do as he is commanded.”[1] The Gospel of God is given then as God’s own antidote. The Law shows up our impotence; the Gospel shows us the Savior. We see what God requires of us, we see how very short we fall, and we learn that God’s grace must carry us forward, if forward we go at all.

But these things are not accomplished by our own splendid “choice”: Luther thought this absolutely fundamental to the message of salvation. God stands behind the dark work of the Law and the life-giving power of the Gospel – not the caliber of our “choice,” or the depth of our understanding, or the intensity of our feeling, or the worthiness of our attitude, or the particular “steps” we follow in formulating our faith. “God’s mercy alone works everything, and our will works nothing,” Luther insisted.[2] If it were not so, Luther continued, “I should… be forced to labor with no guarantee of success, and to beat my fists in the air. If I lived and worked to all eternity, my conscience would never reach comfortable certainty as to how much it must do to satisfy God. Whatever work I had done, there would still be a nagging doubt as to whether it pleased God, or whether He required something more.”[3] Our wills are bound and incapable, it is certainly true: but God’s grace has “abounded all the more” (Romans 5:20).

The Great Commission works in this way, too.

At one level, of course, we receive the Commission as a happy directive, with a sense of adventure and eager expectation. We are honored to be called to the service of the King. We are delighted – and maybe flattered, as well – to be enlisted in the Gospel transformation of the whole wide world. And well we should be. Yet “the plague of impotence” invariably intervenes. What we undertook with joy becomes a burden. What delighted us becomes a load. Maybe you have experienced this phenomenon, yourself. It is perhaps inevitable.

Then we must operate in grace, as Luther advises. God’s mercy works everything and our will nothing.

Erasmus thought Luther’s position nitpicky and unnecessary. Yet when we deviate from this basic Reformation insight, spiritual (and missionary!) calamities will always follow. We come to feel driven, as if our missionary activities make us more acceptable in the sight of God. We come to feel desperate for more and greater activities. We may come to view the people we serve as “notches” in our own drive for success, rather than souls for whom Christ died. Then, yes, what we undertook with joy becomes a burden. Burden is all that remains.

Like every commandment, the Great Commission illuminates our basic spiritual need – not for more resolve or gumption – but for deeper acquaintance with the Savior behind the Commission and greater surrender to his wonderful grace. This is the way actual missionaries are made: ask any missionary with any degree of experience at all. “You can’t force these things,” God told an Old Testament missionary long ago. “They only come about through my Spirit” (Zechariah 4:6, The Message). “God is not disillusioned with us,” Luis Palau said famously. “He never had any illusions to begin with.”[4]

Happily, the Great Commission, like every commandment, does not stand on its own. Jesus invites his disciples to “Come to me…” – before they are sent into the world (Matthew 10:1; Mt. 11:28-30; Mt. 28:16). And he promises to walk with them as they step out with abandon (Matthew 28:20). So don’t go until you come. Don’t slog until you have surrendered and believed. Remember that personal resolve, however resolved you manage to become, is not the cure for the “plague of impotence.” The only cure is Calvary.

2 Ibid., p.78.

3 Ibid., p.313.

4 Luis Palau. BrainyQuote.com, Xplore Inc, 2013. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/l/luispalau202525.html, accessed July 15, 2013.